The Second Anglo-Dutch War was part of a series of four Anglo-Dutch Wars fought between the English (later British) and the Dutch in the 17th and 18th centuries for control over the seas and trade routes.

The Second Anglo-Dutch War was fought between England and the United Provinces from 4 March 1665 until 31 July 1667. England tried to end the Dutch domination of world trade. After initial English successes, the war ended in a decisive Dutch victory. English and French resentment would soon lead to renewed warfare.

Prelude

The First Anglo-Dutch War was concluded with an English victory in the Battle of Scheveningen in August 1653, although a peace treaty was not signed for another eight months. The Commonwealth government of Oliver Cromwell tried to avoid further conflict with the Dutch Republic. It did not come to the aid of its ally, Sweden, when the Dutch thwarted the Swedish attempt to conquer Denmark in the Battle of the Sound. The Commonwealth was at war with Spain and feared Dutch intervention, in part because the Republic contained a strong Orangist party hostile to Cromwell and under the influence of exiled English royalists. However the Treaty of Westminster planted the seeds of future conflict as its secret annex, the Act of Seclusion, forbade the Province of Holland (and by practical extension, any other province of the Netherlands) from installing any member of the House of Orange as their stadtholder.[citation needed]

The Restoration of Charles II, in 1660, produced a general surge of optimism in England. Many hoped to reverse the Dutch dominance in world trade.[citation needed] At first, however, Charles II sought to remain on friendly terms with the Republic, as he was personally greatly in debt to the House of Orange, which had lent enormous sums to Charles I during the English Civil War.[citation needed] Nevertheless, a conflict soon developed with the States of Holland over the education and future prospects of his nephew William III of Orange, the posthumous son of Dutch stadtholder William II of Orange, over whom Charles had been made a guardian by his late sister Mary. The Dutch, in this coordinated by Cornelis and Andries de Graeff, tried to placate the king with prodigious gifts, such as the Dutch Gift of 1660. Negotiations were started in 1661 to solve these issues, which ended in the treaty of 1662, in which the Dutch conceded on most points. In 1663, Louis XIV of France stated his claim to portions of the Habsburg Southern Netherlands, leading to a short rapprochement between England and the Republic as Lord Clarendon, for a time, saw France as the greatest danger.[citation needed]

In 1664, however, the situation quickly changed. Clarendon's enemy, Lord Arlington, became the favourite of the king and began to cooperate with the king's brother James, Duke of York, the Lord High Admiral, in order to bring about war with the Dutch, from which both expected great personal gain. James headed the Royal African Company and hoped to seize the possessions of the Dutch West India Company. The two were supported by the English ambassador in The Hague, George Downing, who despised the Dutch, and reported that the Republic was politically divided between Orangists, who gladly would collaborate with an English enemy in case of war, and a States faction consisting of wealthy merchants that would give in to any English demand in order to protect their trade interests. Arlington planned to subdue the Dutch completely by permanent occupation of key Dutch cities.[citation needed] Charles was easily influenced by James and Arlington as he sought a popular and lucrative foreign war at sea to bolster his authority as king.[4]:65 Many naval officers welcomed the prospect of a conflict with the Dutch as they expected to make their name and fortune in battles they hoped to win as decisively as in the previous war.[4]:66

As enthusiasm for war rose among the English populace, privateers began to attack Dutch ships, capturing about two hundred[citation needed] of them. Dutch ships were obligated by the new treaty to salute the English flag first. In 1664, English ships began to provoke the Dutch by not saluting in return. Though ordered by the Dutch government to continue saluting first, many Dutch commanders could not bear the insult. Still, the resulting flag incidents were not the casus belli, as in the previous war. To provoke open conflict, James already in late 1663 had sent Robert Holmes, in service of the Royal African Company, to capture Dutch trading posts and colonies in West Africa.[4]:67 At the same time, the English invaded the Dutch colony of New Netherland in North America on 24 June 1664, and had control of it by October.[5][6][7] The Dutch responded by sending a fleet under Michiel de Ruyter that recaptured their African trade posts, captured most English trade stations there and then crossed the Atlantic for a punitive expedition against the English in America.[4]:68 In December 1664, the English suddenly attacked the Dutch Smyrna fleet. Though the attack failed, the Dutch in January 1665 allowed their ships to open fire on English warships in the colonies when threatened. Charles used this as a pretext to declare war on the Netherlands on 4 March 1665.

The war was supported in England by much propaganda; the cause célèbre was the previous Amboyna Massacre of 1623. That year, ten English factors, resident in the Dutch fortress of Victoria on Ambon were executed by beheading on accusations of treason. During the trial, the English prisoners were allegedly hung up with cloth placed over their faces, upon which water dripped until the victims inhaled water (this is today called waterboarding). After some time, they were taken down to vomit up the water, only to repeat the experience. The Dutch also allegedly placed candles on the victims' bodies to demonstrate the translucence of the flesh. The English at the time milked the alleged atrocity for all it was worth in a long drawn-out diplomatic incident. The English East India Company published an extensive pamphlet in 1631, setting out its case against the Dutch VOC, and this was used for anti-Dutch propaganda during the First Anglo-Dutch War. Though the matter was supposed to be settled with the Treaty of Westminster (1654), now pamphleteers reminded the public of it as the war neared. Additionally, broadsheets demonized the Dutch as drunken and profane, with Andrew Marvell's 1653 insult of Holland, "The Character of Holland," reprinted ("This indigested vomit of the Sea,/ Fell to the Dutch by Just Propriety"). When De Ruyter recaptured the West African trading posts, many pamphlets were written about presumed new Dutch atrocities, although these contained no basis in fact.[8]: 290-291

The deeper cause of the conflict was mercantile competition. The English sought to take over the Dutch trade routes and colonies while excluding the Dutch from their own colonial possessions. Contraband shipping had gone on from English colonies in America and Surinam for a decade, and the English felt that they were being cheated of their revenues. The Dutch, for their part, considered it their right to trade with anyone anywhere, defending the principle of the mare liberum. However, they enforced a monopoly in the Dutch Indies, and threatened to expand it to India, after having expelled the Portuguese from that region. The vilification of Dutch traders in England was at least partially an expression of unease with the presence of notable Cromwellian politicians and officers in Holland in exile. Charles II had reason to be nervous about the possibility of a Dutch invasion coordinated with an uprising within England. In addition, many members of the English elite would gain personally if Dutch ships were captured.[citation needed]

After their defeat in the First Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch had become much better prepared. Beginning in 1653, a "New Navy" was constructed, a core of sixty new, heavier ships with professional captains. Losses had been consequently replaced after this. However, these ships were still much lighter than the ten "big ships" of the English navy. In 1664, when war threatened, it was decided to completely replace the fleet core with still heavier ships. Upon the outbreak of war in 1665, these new vessels were mostly still under construction, and the Dutch only possessed four heavier ships of the line. During the second war, the new ships were quickly completed, with another twenty ordered and built. England, meanwhile, could only build a dozen ships, due to financial difficulties.[citation needed]

In 1665, England boasted a population about four times as large as that of the Dutch Republic. This population was dominated by poor peasants, however, and so the only source of ready cash were the cities. The Dutch urban population exceeded that of England in both proportional and absolute terms and the Republic would be able to spend more than twice the amount of money on the war compared to England, the equivalent of ₤11,000,000.[4]:79 The outbreak of war was followed ominously by the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London, hitting the only major urban centre of the country. These events, occurring in such close succession, virtually brought England to its knees, as the English fleet had suffered from cash shortages even before these calamities, despite having been voted a record budget of ₤2,500,000 by the English parliament. The navy did not pay its sailors with money, but with "tickets", or debt certificates. Charles lacked an effective means of enforcing taxation. The only way to finance the war, in effect, was to capture Dutch trade fleets. English penury made the war's outcome dependent on the fortunes of its privateers; in fact Dutch privateers would be the more successful.[4]:78

The War

1665

The first encounter between the nations was, as in the First Anglo-Dutch War, at sea. Fighting began in earnest with the Battle of Lowestoft on 13 June, where the English gained a great victory; it was the worst defeat of the Dutch Republic's navy in history. The English, though, were unable to capitalise on the victory.

The leading Dutch politician, the Grand Pensionary of Holland Johan de Witt, quickly restored confidence by joining the fleet personally. Under de Witt, ineffective captains were removed and new tactics formalised. In August De Ruyter returned from America to a hero's welcome and was given supreme command of the confederate fleet. The Spice Fleet from the Dutch East Indies managed to return home safely after the Battle of Vågen, though at first blockaded at Bergen, causing the financial position of England to deteriorate.[4]:70 For every warship the English built during the conflict, the Dutch shipyards turned out seven.

In the summer of 1665 the bishop of Münster, Bernhard von Galen, an old enemy of the Dutch, was induced by promises of English subsidies to invade the Republic. At the same time, the English made overtures to Spain. Louis XIV, though obliged by a 1662 treaty to assist the Republic in a war with England, had postponed his aid on the pretence of wanting to negotiate a peace. Louis was now greatly alarmed by the attack by Münster and the prospect of an English–Spanish coalition. Intent on conquering the Spanish Netherlands, Louis feared that a collapse of the Republic could create a powerful Habsburg entity on his northern border, as the Habsburgs were the traditional allies of the German bishops. He immediately promised to send a French army corps, and French envoys—under the grand name of the célèbre ambassade—arrived in London to begin negotiations in earnest, threatening the wrath of the French monarch if the English failed to comply.

These events caused great consternation at the English court. It now seemed that the Republic would end up as either a Habsburg possession or a French protectorate. Either outcome would be disastrous for England's strategic position. Clarendon, always having warned about "this foolish war", was ordered to quickly make peace with the Dutch without French mediation. Downing used his Orangist contacts to induce the province of Overijssel, whose countryside had been ravaged by Galen's troops, to ask the States-General for a peace with England conceding—so the Orangists naively thought—to the main English demand that the young William III would be made Captain-General and Admiral-General of the Republic and ensured of the stadtholderate. The sudden return of De Witt from the fleet prevented the Orangists from seizing power. In November, the States-General promised Louis never to conclude a separate peace with England. On 11 December it openly declared that the only acceptable peace terms would be either a return to the Status quo ante bellum or a quick end to hostilities under a uti possidetis clausule.

1666

In the winter of 1666 the Dutch created a strong anti-English alliance. On 26 January, Louis declared war. In February, Frederick III of Denmark did the same after having received a large sum. Then Brandenburg threatened to attack Münster from the east. Von Galen, the English subsidies having remained largely hypothetical, made peace with the Republic in April at Cleves. By the spring of 1666, the Dutch had rebuilt their fleet with much heavier ships — thirty of them possessing more cannon than any Dutch ship in early 1665 — and threatened to join with the French.[4]:71 Charles made a new peace offer in February, employing a French nobleman in Orange service, Henri Buat, as messenger. In it he vaguely promised to moderate his demands if the Dutch would only appoint William in some responsible function and pay £200,000 in "indemnities". De Witt considered it a mere feint to create dissension among the Dutch and between them and France. A new confrontation was inevitable.

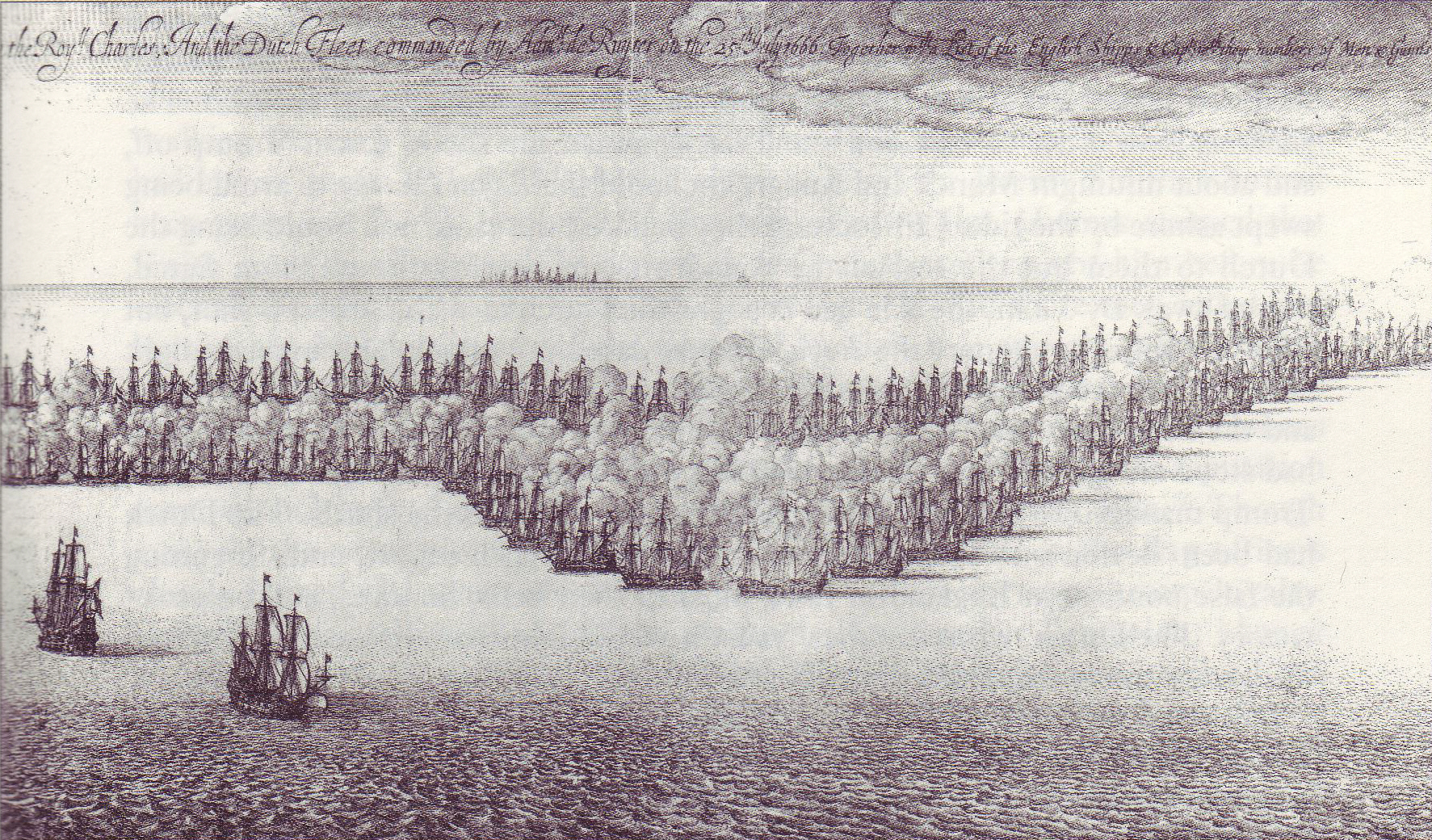

The result was the Four Days Battle, one of the longest naval engagements in history. Despite administrative and logistic difficulties, a fleet of eighty ships, under General at Sea George Monck, the Commonwealth veteran (after the Duke of Albemarle), set sail at the end of May 1666. Prince Rupert of the Rhine was then detached with twenty of these ships to intercept a French squadron on 29 May (Julian calendar), which had been thought to be passing through the English Channel, presumably to join the Dutch fleet.[4]:72 In fact, the French fleet was still largely in the Mediterranean.

Leaving the Downs, Albemarle came upon De Ruyter's fleet of 85 ships at anchor, and he immediately engaged the nearest Dutch ship before the rest of the fleet could come to its assistance. The Dutch rearguard under Lieutenant-Admiral Cornelis Tromp set upon a starboard tack, taking the battle toward the Flemish shoals, compelling Albemarle to turn about, to prevent being outflanked by the Dutch rear and centre, culminating in a ferocious unremitting battle that raged until nightfall.[4]:73 At daylight on 2 June, Albemarle's strength of operable vessels was reduced to 44 ships, but with these he renewed the battle tacking past the enemy four times in close action. With his fleet in too poor a condition to continue to challenge, he then retired towards the coast with the Dutch in pursuit.

The following day Albemarle ordered the damaged ships forward covering their return on the 3rd until Prince Rupert, returning with his twenty ships, joined him.[4]:74 During this stage of the battle, Vice-Admiral George Ayscue, on the grounded Prince Royal — one of the nine remaining "big ships" —, surrendered, the last time in history for an English admiral in battle.[4]:75 With the return of the fresh squadron under Prince Rupert the English now got more ships, yet the Dutch decided the battle on the fourth day, breaking the English line several times. When the English retreated, De Ruyter was reluctant to follow, perhaps because of lack of gunpowder. The battle ended with both sides claiming victory: the English because they contended Dutch Lieutenant Admiral Michiel de Ruyter had retreated first, the Dutch because they had inflicted much greater losses on the English, who lost ten ships against the Dutch four.

One more major sea battle would be fought in the conflict. The St. James's Day Battle on 4 and 5 August, ended in English victory but failed to decide the war as the Dutch fleet escaped certain annihilation. At this stage, simply surviving was sufficient for the Dutch, as the English could hardly afford even a victory.

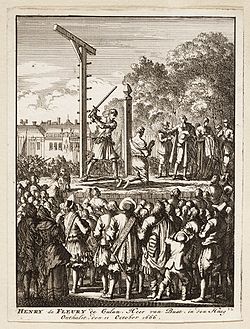

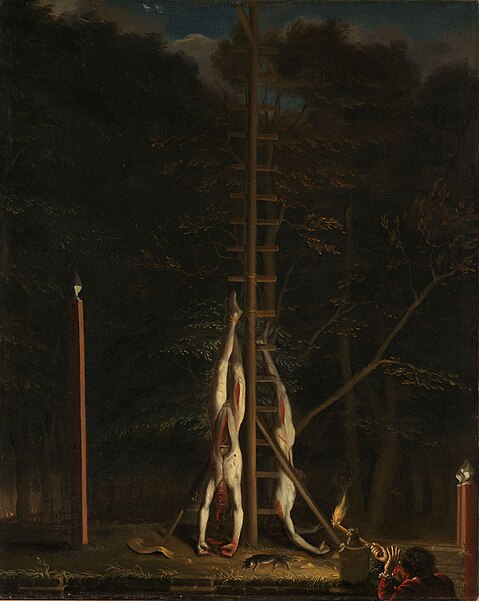

Tactically indifferent with the Dutch losing two ships and the English one, the battle would have enormous political implications. Cornelis Tromp, commanding the Dutch rear, had defeated his English counterpart, but was accused by De Ruyter of being responsible for the plight of the main body of the Dutch fleet by chasing the English rear squadron as far as the English coast. As Tromp was the champion of the Orange party, the conflict led to much party strife; because of this on 13 August Tromp was fired by the States of Holland. Five days later Charles made another peace offer to De Witt, again using Buat as an intermediary. Among the letters given to the Grand Pensionary, by mistake was included one containing the secret English instructions to their contacts in the Orange party, outlining plans for an overthrow of the States regime. Buat was arrested; his accomplices in the conspiracy fled the country to England, among them Tromp's brother-in-law Johan Kievit. De Witt now had proof of the collaborationist nature of the Orange movement and the major city regents distanced themselves from its cause. Buat was condemned for treason and beheaded.

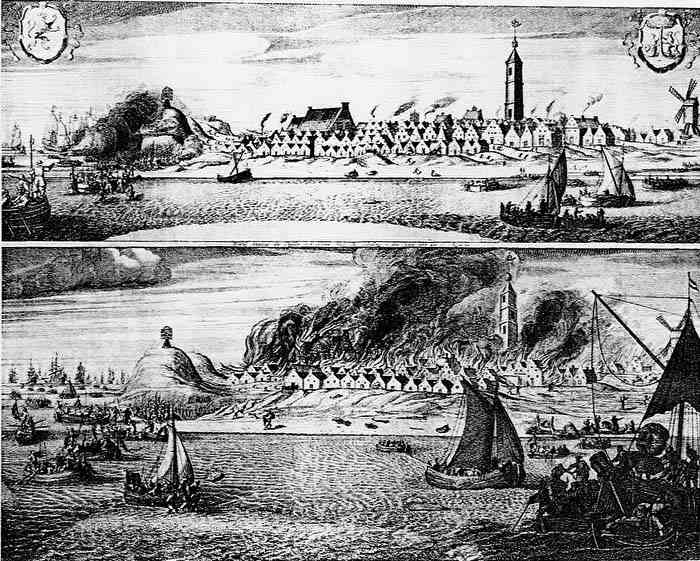

The mood in the Republic now turned very belligerent, also because in August English vice-admiral Robert Holmes during his raid on the Vlie estuary in August 1666, destroyed about 130 merchantmen (Holmes's Bonfire) and sacked the island of Terschelling, setting the town of West-Terschelling aflame. In this he was assisted by a Dutch captain, Laurens Heemskerck, who had fled to England after having been condemned to death for cowardice shown during the Battle of Lowestoft.

After the Fire of London in September, the next peace offer by Charles came, again reducing his demands. Small "indemnities", the return of the nutmeg island of Paulu Run and a deal over India would suffice now; no more mention was made of the position of William. The States-General simply referred to its declaration of 11 December 1665, no longer willing to make a slight concession that would allow Charles to withdraw from the war without losing face.

1667: Medway

Early 1667, the financial position of the English crown became desperate. The kingdom simply lacked the money to make the entire fleet seaworthy, so it was decided in February that the heavy ships would remain laid up at Chatham. Clarendon explained to Charles that he had but two options: either to make very substantial concessions to Parliament or to begin peace talks with the Dutch under their conditions. In March these were indeed started at Breda, in the southern Generality Lands, as negotiations in the provinces themselves would by the conventions of the day be considered a sign of inferiority for the Dutch. Charles, however, did not negotiate in good faith. He had already decided to turn to a third option: becoming a secret ally of France to obtain money and undermine the Dutch position.[4]:76 On 18 April he concluded his first secret treaty with Louis, stipulating that England would support a French conquest of the Spanish Netherlands. In May the French invaded, starting the War of Devolution; Charles hoped, by procrastinating the talks at Breda, to gain enough time to ready his fleet in order to obtain concessions from the Dutch, using the French advance as leverage.

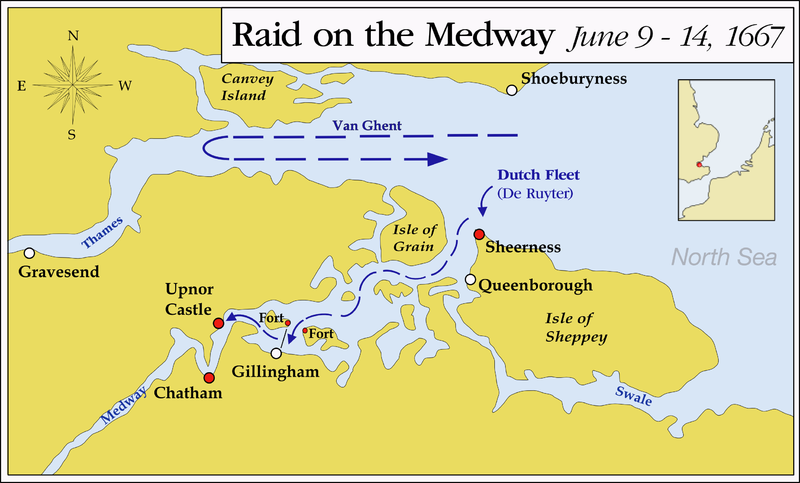

De Witt was aware of Charles's general intentions (though not of the secret treaty). He decided to end the war with one stroke. Ever since its actions in Denmark in 1659, involving many landings to liberate the Danish Isles, the Dutch navy had made a special study of amphibious operations. In 1665 the Dutch Marine Corps (then under the name of Regiment de Marine) had been created. De Witt personally had arranged for the planning of a landing of marines at Chatham. At both the Four Days' Battle and the St James's Day Fight a Dutch marine contingent had been ready to land in the Medway immediately following a possible Dutch victory at sea. Conditions had not allowed for this in either battle, however. But now there was no English fleet of any quality able to contest command of the North Sea. It lay effectively defenceless at Chatham and De Witt ordered it destroyed.

In June, De Ruyter, with Cornelis de Witt supervising, launched the Dutch "Raid on the Medway" at the mouth of the River Thames. After capturing the fort at Sheerness, the Dutch fleet went on to break through the massive chain protecting the entrance to the Medway and, on the 13th, attacked the laid up English fleet. The daring raid remains England's greatest naval disaster.[9] Fifteen of the Navy’s remaining ships were destroyed, either by the Dutch or by being scuttled by the English to block the river. Three of the eight remaining "big ships" were burnt: the Royal Oak, the new Loyal London and the Royal James. The largest, the English flagship HMS Royal Charles, was abandoned by its skeleton crew, captured without a shot being fired, and towed back to the Netherlands as a trophy. Its coat of arms is now on display in the Rijksmuseum. Fortunately for the English, the Dutch marines spared the Chatham Dockyard, England's largest industrial complex; a land attack on the docks themselves would have set back English naval power for a generation.[4]:77A Dutch attack on the English anchorage at Harwich had to be abandoned however after a Dutch attempt made on Fort Landguard ended in failure.

The Dutch success made a major psychological impact throughout England, with London feeling especially vulnerable just a year after the Great Fire (which was generally interpreted in the Dutch Republic as divine retribution for Holmes's Bonfire). This, together with the cost of the war, of the Great Plague and the extravagant spending of Charles's court, produced a rebellious atmosphere in London. Clarendon ordered the English envoys at Breda to sign a peace quickly, as Charles feared an open revolt.

War in the Caribbean

The Second Anglo-Dutch war had spread to the Caribbean islands in 1665 and the English had been quick to capture the Dutch island of Sint Eustatius. A French declaration of war on the side of the Dutch in mid April 1666 took the situation a step further and buoyed a Dutch counterattack. Quickly the French under Joseph-Antoine de La Barre took over the English Caribbean islands offsetting English control. First the English half of St Kitts fell, quickly followed by Antigua and Montserrat. The Dutch meanwhile under Admiral Abraham Crijnssen had reconquered the island of Sint Eustatius and following that captured Suriname. With the Caribbean clearly in Franco-Dutch control Abraham Crijnssen and de La Barre combined forces and agreed to a Franco-Dutch invasion of Nevis on 20 May 1667. However, this invasion was repelled by the English in a confused naval action. After this failed attack and the fallout that followed, the French, under Admiral Joseph de la Barre, moved to Martinique. The Dutch under Crijnssen sailed to north to attack the Virgina colony.

In early June a new British fleet, under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir John Harman, reached the West Indies. Harman brought reinforcements and attacked the French at Martinique and by 6 July virtually sunk, burnt or captured the vast majority of the French ships, 21 in all. Harman with the French fleet neutralized then attacked the French at Cayenne forcing its garrison to surrender and then went on to recapture Suriname by October. These English victories, though absolute, came too late to have any significant impact on the result of the war. Crijnssen sailed back to the Caribbean in horror only to find the French fleet vaporized and the English back in possession of Suriname. However, on 31 July the English and Dutch had signed the Treaty of Breda, and news of this filtered through by the end of October, beginning of November, ending hostilities. Part of the treaty was a stipulation that each side would keep the possessions it held on 31 July, so Surinam again returned to the Dutch.

Peace

On 31 July 1667, the Treaty of Breda sealed peace between the two nations. The treaty allowed the English to keep factual possession of New Netherland (renamed New York, after James), while the Dutch kept control over Pulau Run and the valuable sugar plantations of Suriname which they had conquered in 1667. This temporary uti possidetis solution would be made official in the Treaty of Westminster (1674). The Act of Navigation was moderated in favour of the Dutch.[citation needed]

The peace was generally seen as a personal triumph for De Witt. The Republic was jubilant about the Dutch victory. De Witt used the occasion to induce four provinces to adopt the Perpetual Edict (1667) abolishing the stadtholderate forever. He used the weak position of Charles to force him into the Triple Alliance of 1668 which again forced Louis to temporarily abandon his plans for the conquest of the Southern Netherlands. But De Witt's success would eventually produce his downfall and nearly that of the Republic with it. Both humiliated monarchs intensified their secret cooperation and would, joined by the bishop of Münster, attack the Dutch in 1672 in the Third Anglo-Dutch War. De Witt was unable to counter this attack, as he could not create a strong Dutch army for lack of money and fear that it would strengthen the position of the young William III. That same year De Witt was assassinated, and William became stadtholder.

The peace was generally seen as a personal triumph for De Witt. The Republic was jubilant about the Dutch victory. De Witt used the occasion to induce four provinces to adopt the Perpetual Edict (1667) abolishing the stadtholderate forever. He used the weak position of Charles to force him into the Triple Alliance of 1668 which again forced Louis to temporarily abandon his plans for the conquest of the Southern Netherlands. But De Witt's success would eventually produce his downfall and nearly that of the Republic with it. Both humiliated monarchs intensified their secret cooperation and would, joined by the bishop of Münster, attack the Dutch in 1672 in the Third Anglo-Dutch War. De Witt was unable to counter this attack, as he could not create a strong Dutch army for lack of money and fear that it would strengthen the position of the young William III. That same year De Witt was assassinated, and William became stadtholder.

References

1.

^ Rommelse,

Gijs (2006) The Second Anglo–Dutch War (1665–1667): raison d'état,

mercantilism and maritime strife, Uitgeverij Verloren, p. 184

2.

^ Phillipson,

Coleman (2008) Termination of War and Treaties of Peace, The Lawbook

Exchange, p. 222

4.

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rodger, NAM (2004), The

Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, Penguin.

5.

^ Pomfret,

Charles O (1973), Colonial New Jersey:A History, New York: Charles

Scribner's Sons, p. 22

6.

^ Swindler,

William F., ed. (1973–79), Sources and Documents of United States

Constitutions 6, Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications,

pp. 375–7

7.

^ Van Zandt,

Franklin K (1976), Boundaries of the United States and the Several States,

Geological Survey Professional Paper 909, Washington, DC: United States

Government Printing Office, p. 79

8.

^ Pincus,

Steven C.A. (2002), Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the Making

of English Foreign Policy, 1650 - 1668, Cambridge U.P..

9.

^ “It can

hardly be denied that the Dutch raid on the Medway vies with the Battle of Majuba

in 1881 and the Fall of Singapore

in 1942 for the unenviable distinctor of being the most humiliating defeat

suffered by British arms.” - Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of

the 17th Century, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London (1974), p.39

taken from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Anglo-Dutch_War [31.07.2013]

Ericsson continued his research and invention activities related to engines and maritime propulsion systems. He explored such energy sources as solar, tidal, wind and gravitational power, explorations with relevance to the enduring energy needs of society. In 1876 he compiled and had printed "Contributions to the Centennial Exhibition", a book to describe his many contributions to scientific and technological progress. He believed that he had been slighted when he was invited to display only one of his many inventions at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

Ericsson continued his research and invention activities related to engines and maritime propulsion systems. He explored such energy sources as solar, tidal, wind and gravitational power, explorations with relevance to the enduring energy needs of society. In 1876 he compiled and had printed "Contributions to the Centennial Exhibition", a book to describe his many contributions to scientific and technological progress. He believed that he had been slighted when he was invited to display only one of his many inventions at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.