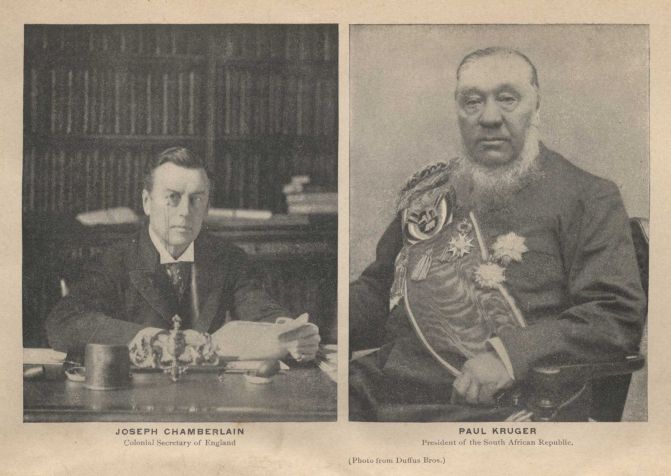

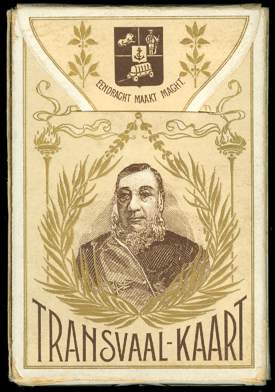

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, and affectionately known as Uncle Paul (Afrikaans: "Oom Paul"), was State President of the South African Republic (Transvaal). He gained international renown as the face of Boer resistance against the British during the South African or Second Boer War (1899–1902).

Kruger was born at Bulhoek, on his grandfather's farm in the British Cape Colony, and he grew up on the farm Vaalbank. He received only three months of formal education. Kruger was one of the first to be confirmed into the Dutch Reformed Church which was established by Daniel Lindley in 1842.[2]

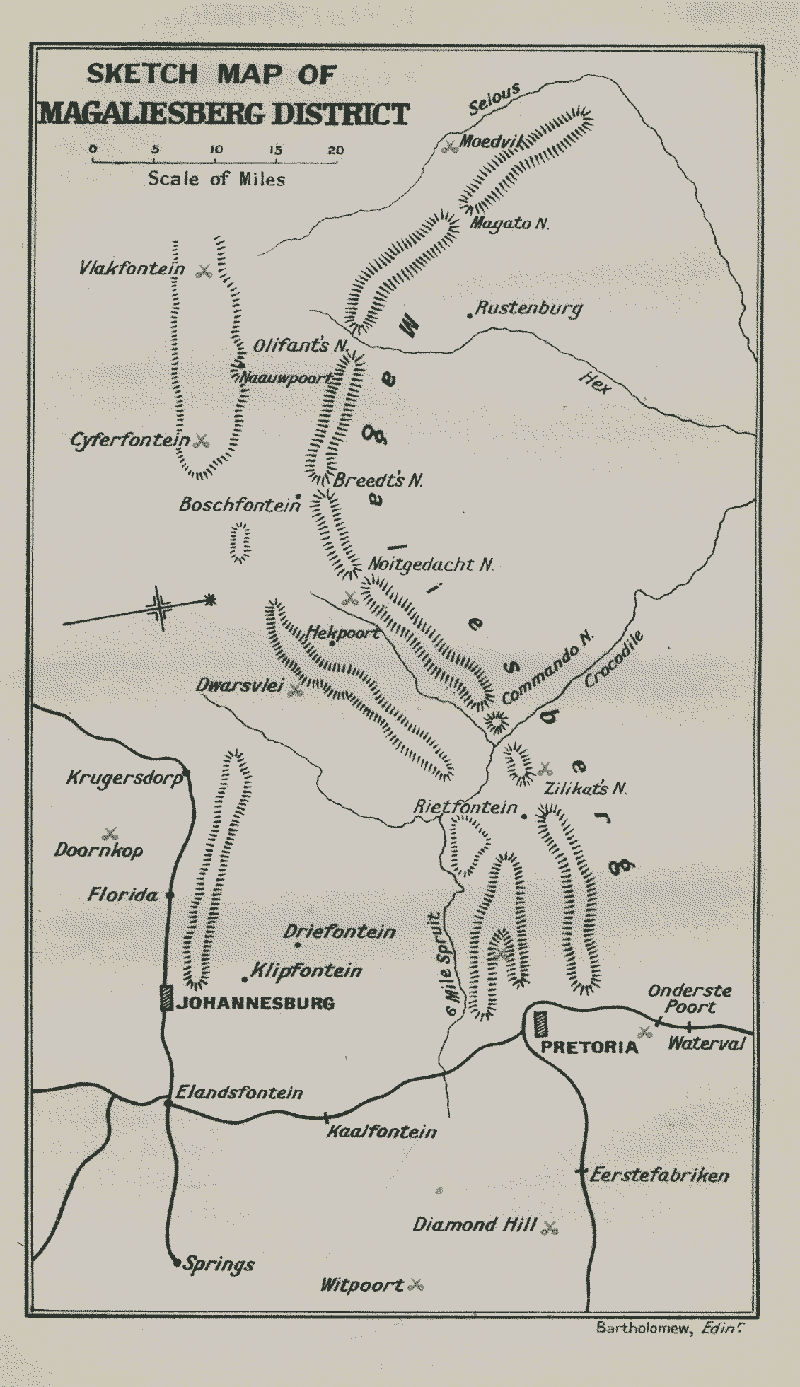

Paul Kruger became proficient in hunting and horse riding. He contributed to the development of guerrilla warfare during the First Boer War. Kruger's father later decided to settle in the district now known as Rustenburg. At the age of 16, Kruger was entitled to choose a farm for himself at the foot of the Magaliesberg, where he settled in 1841.

The following year he married Anna Maria Etresia du Plessis (1826-1846),and they went together with Paul Kruger's father to live in the Eastern Transvaal. After the family had returned to Rustenburg, Kruger's wife and infant died in January, 1846. He then married his second wife Gezina Susanna Fredrika Wilhelmina du Plessis (1831-1901) in 1847, with whom he remained until her death in 1901. The couple had seven daughters and nine sons.

Kruger was a deeply religious man; he claimed to have only read one book, the Bible. He also claimed to know most of it by heart. He was a founding member of the Reformed Church in South Africa .

Leadership

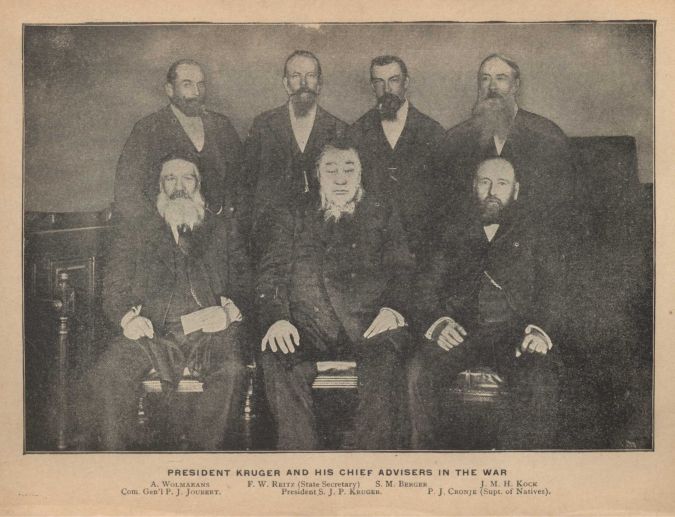

Kruger began his military service as a field cornet in the commandos and eventually became Commandant-General of the South African Republic. He was appointed member of a commission of the Volksraad, the republican parliament that was to draw up a constitution.

People began to take notice of the young man and he played a prominent part in ending the quarrel between the Transvaal leader, Stephanus Schoeman, and M.W. Pretorius.

He was present at the Sand River Convention in 1852.[3]

In 1873, Kruger resigned as Commandant-General, and for a time he held no office and retired to his farm, Boekenhoutfontein.

However, in 1874, he was elected as a member of the Executive Council and shortly after became the Vice-President of the Transvaal.

Following the annexation of the Transvaal by Britain in 1877, Kruger became the leader of the resistance movement. During the same year, he visited Britain for the first time as the leader of a deputation. In 1878, he formed part of a second deputation. A highlight of his visit to Europe was when he ascended in a hot air balloon and saw Paris from the air.

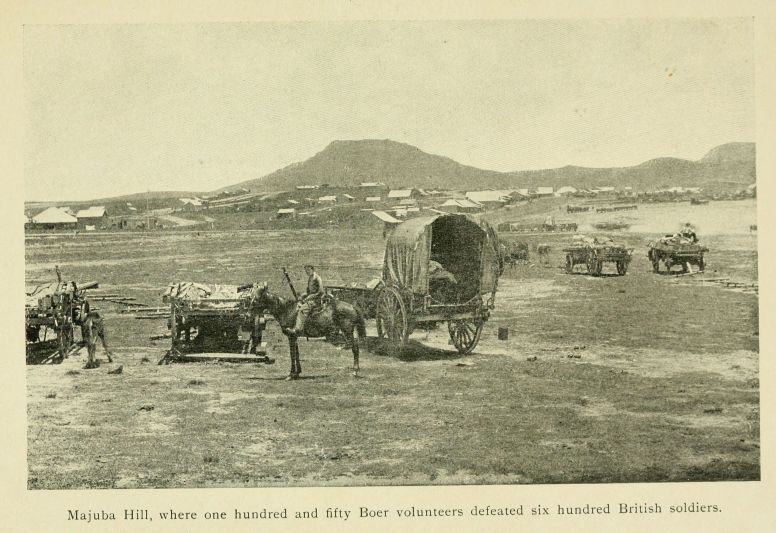

The First Boer War started in 1880, and the Boer forces were victorious at Majuba in 1881. Once again, Kruger played a critical role in the negotiations with the British, which led to the restoration of the Transvaal's independence under British suzerainty.

On 30 December 1880, at the age of 55, Kruger was elected President of the Transvaal. One of his first goals was the revision of the Pretoria Convention of 1881; the agreement between the Boers and the British that ended the First Boer War. In April 1883 he defeated Piet Joubert in the presidential elections.

That year he again left for Britain, empowered to negotiate with Lord Derby. Kruger and his companions also visited the Continent, and this became a triumph in countries such as Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Spain. In the German Empire he attended an imperial banquet at which he was presented to the Emperor, Wilhelm I, and spoke at length with Otto von Bismarck.

Kruger went on to win presidential elections in the 1888, 1893 and 1898, each time defeating Joubert.

In the Transvaal, things changed rapidly after the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand. This discovery had far-reaching political repercussions and gave rise to the uitlander (Afrikaans: foreigner) problem, which eventually caused the fall of the Republic. Kruger acknowledged in his memoirs that General Joubert predicted the events that followed afterwards, declaring that instead of rejoicing at the discovery of gold, they should be weeping because it will "cause our land to be soaked in blood".

At the end of 1895, the failed Jameson raid took place; Jameson was forced to surrender and was taken to Pretoria to be handed over to his British countrymen for punishment.

Joshua Slocum's sailing memoir relates that, on a side journey visiting Pretoria in 1897 on his solo round-the-world trip, he was introduced to Kruger, who, as a religious fundamentalist, exclaimed: "You don't mean round the world, it is impossible! You mean in the world. Impossible!".[4]

In 1898, Kruger was elected President for the fourth and final time.

Exile

On 11 October 1899, the Second Boer War broke out. On 7 May the following year, Kruger attended the last session of the Volksraad, and he fled Pretoria on 29 May as Lord Roberts was advancing on the town. For weeks he either stayed in a house at Waterval Onder or in his railway carriage at Machadodorp in the then Eastern Transvaal, now Mpumalanga. In October, he left South Africa and fled to Mozambique. There he boarded the Dutch warship Gelderland, sent by Queen Wilhelmina, which had simply ignored the British naval blockade of South Africa. He left his wife, who was ill at the time, and she remained in South Africa where she died on 20 July 1901.

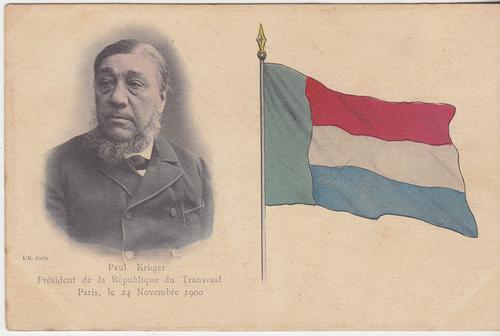

Kruger went to Marseille and from there to Paris. On 1 December 1900 he travelled to Germany, but Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to see him. From Germany he went to The Netherlands, where he stayed in rented homes in Hilversum and Utrecht. He also stayed twice in Menton, France (October 1902 to May 1903 and October 1903 to May 1904) [5] before moving to Clarens, Switzerland, where he died on 14 July 1904.

His body was embalmed by Prof. Aug Roud and first buried on 26 July 1904 in The Hague, Netherlands. After the British government gave permission he was reburied [6] on 16 December 1904 in the Heroes' Acre of the Church Street cemetery, Pretoria.

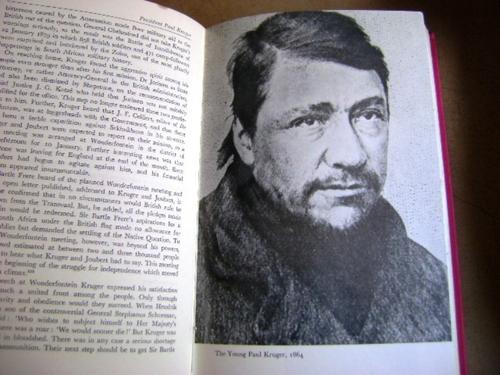

Physical appearance

Kruger was a large squarely built man, with dark brown hair and brown eyes. As he aged, his hair went snowy white. He wore a moustache and full beard when he started to play a role in public life, but in later years a chinstrap beard and no moustache.[7] Martin Meredith cited W. Morcom's statement that he had very oily hair and sunken eyes.[8] He was most often dressed in a black frock coat with a top hat. Never far from his pipe, he was a chain smoker. The image of Kruger in his top hat and frock coat, smoking his pipe was used to great effect in the Anglo-Boer war by British cartoonists.

According to legend, he was named Mamelodi'a Tshwane (Tswana: "whistler of the Apies River") by the inhabitants of the surrounding area for his ability to whistle and imitate bird calls.

Notes

- Jump up ^ Paul Kruger

- Jump up ^ "Daniel Lindley". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Jump up ^ Martin Meredith, Diamonds Gold and War, (New York: Public Affairs, 2007):75

- Jump up ^ 18, Sailing Alone Around the World, by Joshua Slocum, 1900 at www.eldritchpress.org

- Jump up ^ Louis Changuion, Fotobiografie; Paul Kruger 1825–1902, Perskor Uitgewery, 1973, p.132 to 173.

- Jump up ^ Louis Changuion, Fotobiografie; Paul Kruger 1825–1902, Perskor Uitgewery, 1973, p.182 to 196.

- Jump up ^ Louis Changuion, Fotobiografie: Paul Kruger 1825 -1904, Perskor Uitgewery, 1973, p.9-15

- Jump up ^ Martin Meredith, Diamonds, Gold and War: The British, the Boers, and the making of South Africa, Philadelphia: Simon and Schuster UK ltd. 2007. p.78-79

No comments:

Post a Comment