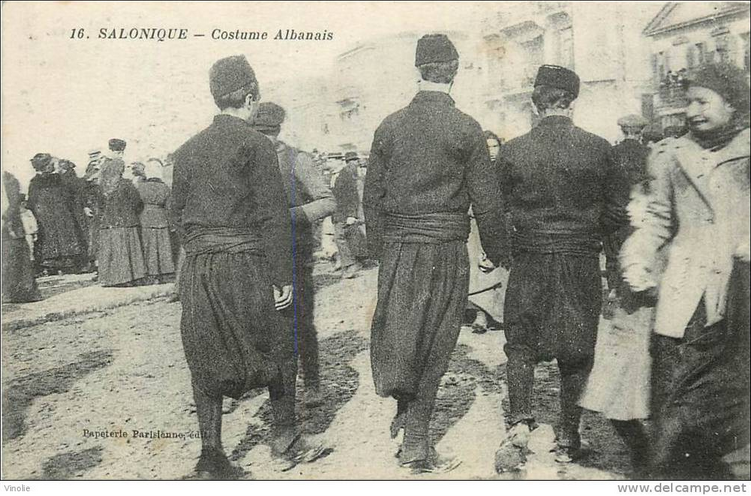

After completing their

conquest of Serbia and Montenegro, the Austro-Hungarian army turns its

attentions toward Albania, occupying the coastal city of Durazzo on the

Adriatic Sea on February 27, 1916.

Durazzo, also known as Durres,

had served as an important port in the region since the 5th century, when it

was part of the Roman empire. After an invasion by the Ottomans at the end of

the 14th century, many Albanians immigrated to Italy; a majority of those who

stayed behind converted to Islam.

The end of the 19th century

saw an explosion of nationalist fervor in Albania and a number of revolts

against Ottoman rule. The country's neighbors, Serbia and Greece, were poised

to divide up Albania between them after the withdrawal of the Turks. Not

wanting this to happen, the Great Powers of Europe—Germany, Great Britain,

France, Austria-Hungary and Russia—appointed a special commission to set the

boundaries of post-Ottoman Albania, in the process stripping the country of 40

percent of its population and more than half its territory, including Kosovo

(which became part of Serbia) and Cameria (which went to Greece).

Despite having previously

recognized Albanian independence, the Great Powers also appointed a German

prince, Wilhelm of Wied, as the country's ruler. Just months after Prince

Wilhelm's arrival, in March 1914, World War I broke out in

Europe, and the prince was forced to flee Albania in the face of strong local

opposition.

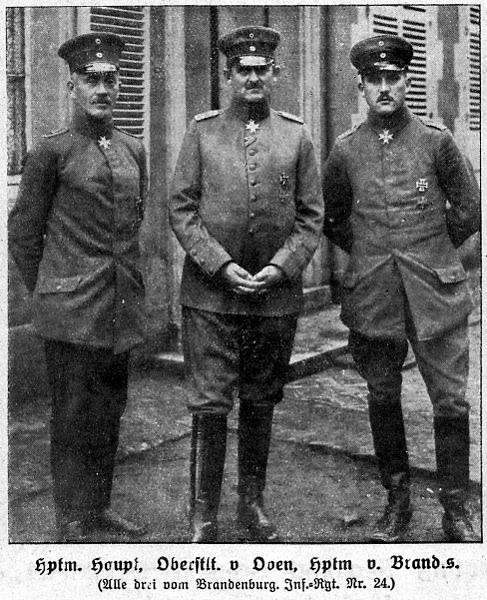

Albania soon became a

battleground for the Allies and Central Powers in the Great War. In 1915,

Durres was occupied by the Italians, who called it Durazzo. As the armies of

the Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary, stormed through the Balkans,

taking control of both Serbia and Montenegro, thousands of Serbs sought escape

through Albania, where the Italians and other Allies helped them evacuate to

the island of Corfu, in the Adriatic Sea, where the Serbian provisional

government was established.

On the verge of the Austrian

invasion of Durazzo, Italian forces killed some 900 mules and donkeys before

evacuating the town; Durazzo's Albanian inhabitants fled en masse as well. The

leader of Albania, Essad Pasha, moved to Naples and set up a provisional

Albanian government. Austria would occupy Durazzo until the end of the war, in

late 1918.

At Versailles, the country's

fate was again in the hands of other European powers. Albania appealed to the

victorious Allies, especially the United States,

to preserve their independence in the face of claims from Serbia, Montenegro,

Italy and Greece. After much haggling, Albania was admitted to the newly formed

League of Nations in 1920 as an independent state, with its borders virtually

the same as they had been before the war.

Taken from: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/austrians-occupy-durazzo-in-albania

[27.02.2015]

.png)